- Home

- Jan Anderson

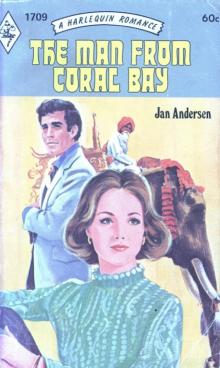

The Man From Coral Bay

The Man From Coral Bay Read online

The man from Coral Bay by Jan Andersen

Rossi's brother Tom, out in Ceylon, had run into some domestic difficulties, and had begged Rossi to go there for a few weeks to help him out. And there she met Matt Lincoln, who was responsible for the domestic difficulties —and all Tom's other problems too . . .

PRINTED IN CANADA

OTHER Harlequin `Romances by JAN ANDERSEN

1387—THE HOUSE CALLED GREEN BAYS 1499—THE SILENT MOON 1532—THE MAN IN THE SHADOW 1709—THE MAN FROM CORAL BAY

Many of these titles are available at your local bookseller, or through the Harlequin Reader Service.

For a free catalogue listing all available Harlequin Romances, send your name and address to:

HARLEQUIN READER SERVICE,M.P.O. Box 707, Niagara Falls, N.Y. 14302 Canadian address: Stratford, Ontario, Canada or use order coupon at back of book.

Original hard cover edition published in 1972 by Mills & Boon Limited

@Jan Andersen 1972

ISBN 373-01709-A

Harlequin edition published August, 1973

All the characters in this book have no existence outside the imagination of the Author, and have no relation whatsoever to anyone bearing the same name or names. They are not even distantly inspired by any individual known or unknown to the Author, and all the incidents are pure invention.

The Harlequin trade mark, consisting of the word HARLEQUIN and the portrayal of a Harlequin, is registered in the United States Patent Office and in the Canada Trade Marks Office.

CHAPTER I

To Ceylon?' Rossi echoed, staring at her mother across the breakfast table. ' But I don't think I want to go just at this moment. Anyway, surely it would be better if Julia brought the children home with her.'

Mrs Finch regarded Rossi with the sort of patient look all mothers give to daughters whom they think are being particularly dense. She tapped the sheet of airmail in front of her. ' Darling, the letter is here. You've read it. For some reason best known to himself Tom doesn't want the children disturbed. And we both know that when Tom gets an idea in his head it takes a lot to shake it out. Anyway, if Julia is ill, then presumably she's not able to look after Sue and Terry.'

Rossi sighed, knowing her rebellion would be short-lived, simply because it was her brother Tom who was involved. He was eight years older than she was and wherever he beckoned, she followed. It had been like that ever since she was a child and when their father died he had somehow filled that role too—until he had suddenly upped and gone to Ceylon.

You always said you wanted to go to Ceylon,' Mrs Finch pointed out, and now you're being offered a free ticket.'

I know, but I suppose I thought of a holiday, or something like that.' Rossi pushed her dark, flyaway hair away from her face.

Well, it will be more or less. I remember Julia telling us they had four servants—or was it five? We know there's a nanny, because we're always

hearing about her.'

Rossi's thoughts started to drift and for once she watched her mother clear the table without offering to help. Perhaps it was a good idea to have a complete break. She had been feeling restless lately, what with some mild dissatisfaction with her job and the growing knowledge that she and Andrew would never make a go of it. Perhaps slipping away like this would mean no harsh words, no recriminations and, most of all, no regrets.

A small, rather neatly built girl, she had a natural buoyancy that was appealing. She found it difficult to hide her feelings. When she smiled—which was often—she was happy, but uncertainty showed in wide sea green eyes.

She picked up Tom's letter and read through the small, spidery writing again. It seemed that Julia was suffering from some severe kind of nervous exhaustion, possibly brought on by the heat, Tom said vaguely, and had been ordered back to England by her doctor for a complete rest and change of climate. She would be going straight down to Devon to stay with her parents and not stopping in London at all. While the nanny was quite reliable with the children he did not feel he wanted to leave her in sole charge for such a long period, particularly as he was away up country a lot these days and she tended to take the easy way out and spoil them. He knew it was a lot to ask of Rossi, but if she could come out for a couple of months to keep an eye on things generally, it would take a great weight off his mind. It was typical of Tom to assume her answer would be yes, because he added that he had tentatively booked a flight for her in ten days' time. He ended by saying he had written to some great friends of his, the Hales, who were home on leave in Sussex

and would give her all the help she needed about clothes, etc.

Rossi looked at the letter for a long minute, then abruptly got to her feet and followed her mother into the kitchen.

' You know,' she said cautiously, ' I think there's something funny going on.'

Funny, dear? What on earth do you mean? I thought the whole tone was very worrying.'

' Silly! I meant funny-peculiar Look, as far as I can tell, Julia must be coming back to England within the next four or five days. See, he says here that if I come on the fourth it will mean the kids will only be on their own for about a week.'

Her mother was looking perplexed. I don't follow you, Rossi. You're off on one of your tangents.'

No, I'm not, I'm just trying to work things out. You're the one who says that Tom never does anything without a reason. I'm just wondering why, if Julia is landing at Heathrow and we're less than an hour away, he doesn't suggest she and I meet before she's whisked off to Devon. After all, presumably she can tell me far more about the house and the sort of luggage I have to take than ever these people the Hales can. And wouldn't you think she'd be dying to give me instructions about the children? After all, I hardly know them, do I?'

Mrs Finch thought for a moment. Perhaps she isn't well enough.'

If she's well enough to travel six thousand miles from Ceylon, then she's well enough to talk to me at the airport for half an hour. Tom must realise there are heaps of questions I want to ask her about the children. No, for some reason, Tom doesn't want us to meet. I'm convinced of that. Why else does he carefully avoid telling us what day she arrives?

I've a good mind to ring up the airport and see if I can find out.'

No,' said Mrs Finch firmly, I don't think you should. Besides, you're jumping to conclusions as usual. It could just as likely be that Julia doesn't want to see anyone. If she's ill . . . and she always was rather a reserved girl. These people the Hales will be able to tell you all you want to know.'

It was a signal for the phone to ring. And of course it had to be Mrs Hale.

She sounded a very warm, pleasant sort of woman and was most insistent that Rossi should come down to Wadhurst for the weekend.

' Timing couldn't be better,' she explained, we're having a small party on Saturday night. Lots of ex-Ceylon people live around here and we've also got a couple of planters home on leave, so we thought it was a marvellous excuse to talk shop. Come down on Saturday for tea and stay over Sunday if you can manage it. Tom tells me he wants me to give you all the tips I can think of. I'll do my best, but of course Julia. . . .' She stopped, as if entering a forbidden subject, and instead hastily started to give travelling directions.

So, two days later, Rossi found herself driving through the wintry countryside. It had snowed about a week ago and while the last slush had disappeared from the London streets within a couple of days, here a thin white film covered the bare fields, and in sheltered spots blackened drifts clung to the roadside. A bitter wind, racing against the roof of the car, made Rossi shiver and turn up the heater. At least there could be no better time of year to be flying off to Ceylon.

Fat Hale proved to be as nice as she had sounded on the phone. A

plump, rather jolly woman in her

thirties, she loved to talk about Ceylon, where it seemed she had lived since she was twenty. Her home was full of all the treasures she had brought back with her over the years; a large ebony elephant with massive ivory tusks, beautiful batik paintings, the kind of thing, she explained, that Rossi would see plenty of in Ceylon; carved wood and strange bronze figures that were supposed to be four hundred years old, and on one wall there was a collection of masks, brightly-coloured, evil-looking things.

In contrast, her husband Jack was quiet, with a very dry sense of humour, rarely talking except when he was asked a direct question; although, Rossi decided, he didn't get much chance to talk when his wife was around. Both of them seemed devoted to Tom, talking about him and the children, but noticeably hardly mentioning Julia.

Over tea Pat Hale said, Tom's had a real run of bad luck this year. Everything he touches seems to go wrong. He's beginning to think he's some kind of Jonah. He often talks about you, so it's marvellous that you're going out there. He needs some sort of stabilising influence, someone to worry about him, instead of him doing all the worrying. We both said before we came home on leave that Julia was. . . Just as she had done on the telephone she stopped abruptly and busied herself with the teapot.

Aware of the sudden change of atmosphere, Rossi said carefully, How long have you been home?'

' A month. Just over a month. It's the worst time of year for us. Just think of it—leaving a temperature of near ninety to plunge down to this! '

But Rossi did not want to talk about the weather. Do you know Tom and Julia well?' she asked.

Oh yes.' Pat Hale pushed a strand of hair away

from her forehead. Jack works in the same office as Tom.'

' Worked, you mean,' her husband corrected quietly, it's two months since Tom left.'

Rossi opened her mouth, then closed it again. Something stopped her saying that neither she nor her mother knew that Tom had changed his job. He had been with the same firm most of his working life.

And Julia?' she said instead. Of course you must know her well, then. My mother and I are worried about her. Tom's a bad letter writer. All he's said is that she's suffering from nervous exhaustion. Can you tell me any more than that?'

The glance that Pat Hale shot at her husband was so swift that Rossi wondered if she had imagined it. But she hadn't—she was almost sure of it.

Just a shade too casually Pat said, Oh, Julia's not really a mixer. She tends to keep herself to herself. I think that's why her nerves have got on top of her. And maybe the climate doesn't really suit her. You need the right sort of temperament to live in the East.'

' And Julia hasn't got it?'

Pat shook her head. ' I'm only guessing. I only know she seems rather unhappy. Some of us have tried to help her, but she shuts us out. Still, I expect you know your own sister-in-law better than we do.'

Rossi admitted that she didn't. You see, Tom married Julia at the end of one of his leaves. We hardly knew her then and they had their honeymoon on board ship returning to Ceylon. Since then I've only met her during the last two leaves.' Because of her instinctive loyalty to Tom she did not admit that she had found Julia a little standoffish nearly two years ago.

Pat Hale seemed to take this as a signal to launch into confidences about Julia. She leaned slightly forward. Oh, well, then you won't even know that Julia has made Tom's life quite impossible lately —and he with all his other problems, like leaving his job and starting the project up on the north coast.'

This time Rossi did not see the quick glance, she only sensed it, and she knew it had come from Jack Hale, as if he were warning his wife that she had said quite enough already. Rossi felt a small shiver of apprehension. There was something going on between Tom and Julia, something she knew nothing about.

Pat glanced hastily at her watch. ' Heavens, it's half past five, and I've still got a million things to do before the guests arrive.'

Can I help?' said Rossi.

No, really, thank you, at least not at the moment. You just make yourself at home, and then you can have a nice long luxury bath. I did all the food earlier, so there are really only the finishing touches and I want to check that I haven't forgotten anything. I'll call you if I need a hand, really I will.'

On impulse Rossi said, ' May I use the phone? There's something I've forgotten to do.'

Of course. It's in that little cubbyhole just at the end of the hall. All the telephone books are there and it's reasonably private.'

Rossi got through to Overseas Passenger Enquiries at London Airport and learned that the next flight in from Colombo was on the following day about noon. No, they were afraid they had no details yet about passenger lists. They did not receive those until the last minute.

Rossi put down the phone slowly. Her mind was

made up. She was going to try to see Julia. She worked it out that it was unlikely she would have arrived today; it would be most probably tomorrow or Monday. And with only one flight a day, surely she could catch her. Anyway, it seemed worth a

try.

The party that evening was a strange, unreal affair. There were about eighteen guests and with the exception of herself all had either lived in Ceylon, had visited there, or were home on leave. It was a little like an old school reunion, with only one topic of conversation. While they were all perfectly polite to her she recognised the wavering glances, the lack of personal interest that made her feel distinctly like an outsider. She began to feel rather bored.

' You don't look as though you belong.' The voice, rather light, yet firm in texture, came from behind her.

She swung round to find a young, fair-haired man with a roguish twinkle in his eye, grinning at her.

Before she could reply he said, No, don't tell me, you're not one of the Ceylon gang, that's your trouble.'

You're right,' she agreed ruefully, ' I feel a bit like a fish out of water. But I'll be able to join what seems like a very exclusive club in just about a week.'

Then you must be Tom Finch's sister. Someone has just said that you were going out there to join him. Here,' he took her glass from her hand, let me get you another drink while you grab those two seats over there. At least if we can't talk about Ceylon, we can talk about Tom.'

She watched him ease his way across the room, a thin, wiry man, who moved lightly and talked

easily to the people who waylaid him. Unconsciously she smoothed her hair into place and hoped she wasn't really as pale as she felt among these tanned, outgoing people.

He brought back fresh drinks, then dropped into the seat beside her.

Now,' he said cheerfully, let's introduce ourselves properly. I'm Barney Lawrence, a rather indifferent manager of a tea plantation somewhere towards the south of the island.'

And you really know Tom well? I suppose I shouldn't be surprised. Someone was telling me earlier that everyone who's in tea knows everyone else.'

' That's just about it these days. There aren't so many of us left. Now, your name please, Tom's sister.'

She found herself relaxing really for the first time that evening. It's Rosamund,' she told him, but I've been known as Rossi ever since I can remember.'

Then hello, Rossi. I'll look forward to seeing you in Ceylon. I'm right on the tail end of my leave, so I'll be back any minute. And with this weather, frankly, I can't get there quickly enough. Are you going for a holiday?'

Not really. I'm going to look after Tom's children while Julia comes home . . . for a rest.'

Ah, yes, the enigmatic Julia. So she's coming home after all.'

Her eyes flicked towards his. ' What do you mean by that?'

He raised his shoulders and let them drop expressively. Nothing really. No, that's not strictly true. You see, with the British population shrinking, nowadays Ceylon grows more and more like a

scattered village. Therefore everyone likes to know all about everyone else. It's difficult out there to be " different " . You stick ou

t like a sore thumb. And Julia's different. We all know Tom so well, but we don't know her; not really, anyway. I don't think she likes the country, and yet I'm not completely sure. You see,' he smiled wryly at her, ' because we don't know, we tend to make up our own stories. There, at least I'm being honest with you.'

' Barney,' she said slowly, ' if I asked you a straight question, would you give . me a straight answer?'

He cocked his head on one side, regarding her with a wide brown-eyed gaze in which she could read nothing. ' Well now, having claimed to be honest, I'll have to try, won't I? Go on, fire away.'

Why is it that people don't seem to like Julia?'

He leaned back against the sofa as if that was the last question he expected to be asked. She wasn't sure if she detected relief.

' Now, what on earth makes you think that?'

' You see,' she said quietly, ' you not only haven't answered my question, you've asked another one.'

' All right,' he returned bluntly, ' then I'll do my best. It isn't that people don't like Julia, it's that she doesn't want to know them. You should know yourself, Rossi, that if you put out a hand to help someone in need and that hand is knocked away without explanation, you'd have to be a saint to run after that person, or even to take a deep breath and try again. Well, that's Julia, I suppose. Probably she is unhappy, but if she won't let us help her, then we can't find out what's wrong. Mind you, I say we, but I'm really the last person to ask. I live in the hills north of Kandy and I'm only in town rarely, but—well, I've known Tom a hell of a long time

and I don't like to see him going downhill, getting grouchy and turned in on himself. I reckon a few months in Europe for Julia will fix things between them. She probably needs a good rest in a more equable climate and—well, I daresay Tom will also get things in perspective. And with nothing else to worry him he may even be able to get his new project on its feet.'

' What is his new project?' Rossi asked eagerly. Pat mentioned it, but I never really had a chance to ask.'

The Man From Coral Bay

The Man From Coral Bay